Table of Contents

Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyaan - Making India Self-Reliant!

Hon'ble Prime Minister Narendra Modi has proposed a special economic package for an Atmanirbhar India in his address on May 12, 2020. At INR 20 lakh crore, the complete financial package of Atmanirbhar India is around 10% of India's Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

It isn't a case of protectionism and does not have an internal focus. Import substitution and economic nationalism are not the two prime things. Instead, it is the method used by the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government to discuss and justify its Atmanirbhar Bharat agenda.

The Indian government is taking several actions to ensure that people are well-prepared to meet the challenges and threats post COVID-19.

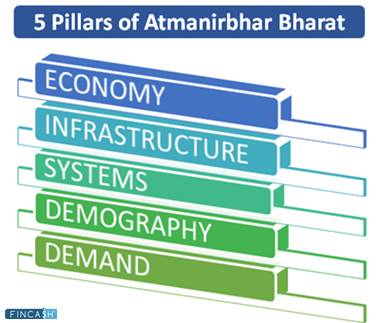

5 Pillars of Atmanirbhar Bharat

India's self-sufficiency is based on five pillars, as follows:

- Economy: Quantum leaps, not incremental adjustments, has to be the order

- Infrastructure: It is a symbol of modern India

- Systems: Technology-driven systems must be there

- Demography: It is the world's largest democracy's vibrant demography

- Demand: Making the most of the power of supply and demand is essential

5 Phases of Atmanirbhar Bharat

Atmanirbhar Bharat is divided into five phases:

- Phase I: Small and medium-sized businesses (MSMEs)

- Phase II: Poor people, especially migrants and farmers

- Phase III: Agriculture

- Phase IV: New Growth Horizons

- Phase V: Enablers and Government Reforms

Talk to our investment specialist

An All-in-One Economic Package

The economic package is worth INR 20 lakh crore when combined with earlier statements by the government during the COVID-19 pandemic and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) measures to inject money into the economy.

The package aims to provide the MSMEs and the cottage Industry in India with much-needed financial and policy help. Under the 'Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyaan,' the government of India has also proposed a slew of radical changes aimed at attracting investment, improving the ease of doing business, and bolstering the Make in India drive.

Achieving the Goal of Atmanirbhar Bharat

As an initial step, the government has created Performance Linked Incentive (PLI) programmes for industries that rely heavily on imports. This will aid India in developing a domestic supply chain for products that will be crucial in the future, such as electronic products (including smartphones) and active pharmaceutical components.

It has also expanded the initiative to include major exporting industries such as textiles, which lack an understanding of manmade fabrics. The PLI scheme, according to analysts, is projected to propel India's Manufacturing growth in the following years.

However, developing the ecosystem requires India to rule the world and the country should entail more than simply filling supply chain gaps. It will assist if you have a better knowledge of what Atmanirbharta means.

Issues Faced by Indian Enterprises

Looking at the other side, it is quite apparent that apart from their reliance on imports, Indian enterprises are hampered by several variables that put them at a distinct disadvantage compared to their global counterparts. They, too, must be addressed, like the ones mentioned below:

Costs of Production

India isn't precisely a low-cost manufacturing base. Although it is less expensive than established economies, other emerging economies fare better. To illustrate well, let’s consider the cost of electricity. It costs 11 cents for one unit in India in comparison to 8 cents in Vietnam and 9 cents in China.

In actual terms, labour costs are low, but India lags well behind China, South Korea, and Brazil when productivity is considered. Apart from that, India is ranked 107th in the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) in terms of skillset, compared to China standing at 64th and South Korea at the 27th position. Vietnam is ranked 93rd, while Brazil is placed 96th. As a result, Indian businesses are being pushed to pay more on employee training.

Logistics Costs

At 14% of GDP, India's logistics costs are three times higher than its developed-world peers, which are standing anywhere between 6-8%. Due to the high level of outsourcing in India, logistics costs primarily refer to transportation costs, whereas in advanced countries, they also encompass procurement, planning, and warehousing.

Regulatory and Other Compliance Costs

Indian businesses face substantial regulatory and other compliance costs. Despite the government's efforts to minimise it through digitisation, it remains high, putting enterprises at a competitive disadvantage on the global stage.

Investment in Research & Development

Over the years, total investment in research, development, and innovation has decreased. The defence and space sectors account for the majority of R&D spending.

It's in the auto and pharmaceutical industries in the private sector. But, again, most of it is 'catch-up' with what others have already developed. There is a lack of investment in cutting-edge technologies.

High-Interest Rates

While India may be experiencing low-interest rates, the cost of borrowing in India is higher than in the United States or Japan. The Indian products can only compete globally if interest rates go down.

Trade Policies

To be more competitive and attract investors, countries like Vietnam and Bangladesh are signing trade agreements. When it comes to such deals, India's track record is dismal. After 16 negotiations, the India-EU Free Trade Agreement has been stalled in limbo for the past seven years. Over the last eight years, after nine rounds of talks, Australia's Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement is dead in the water.

Solving these Issues

While there are no upfront solutions to these problems, here are some things that can be considered:

State governments can give up cross-subsidising power to reduce power costs. It will also urge investments to promptly and cost-effectively remove coal from mines.

A renewed focus on skilling and re-skilling is required. There is a need to identify and train workers with emerging skill sets. To increase productivity, labour reforms must be pushed forward.

To save logistics costs, the government should support and incentivise outsourcing. Companies that outsource more than simply transportation enjoy positive outcomes due to improved visibility and asset utilisation. There should also be infrastructural investments to drastically decrease the 2.62-day turnaround time at Indian ports.

Governments (both central and state) must live within their means and, more significantly, avoid populism to cut interest costs. They should also assure solid businesses have unrestricted access to low-cost Capital worldwide. Both governments must adopt a give and take policy to sign trade agreements and avoid being blocked by domestic interests.

India will not be a significant competitor in the global Market unless these challenges are addressed thoroughly. To put it another way, Atamanirbharta will continue to be a pipe dream. If the government is serious about putting this economic ideology into practice, it should explicitly identify areas that need improvement for Indian manufacturing to be competitive. It should also go further and state the magnitude of progress and the timeline for achieving it.

After this, necessary policies can be drafted and implemented to effect the transformation. Furthermore, such a statement will dispel any ambiguity in the minds of trade partners, investors, and others who have struggled to comprehend the strategy.

Final Words

India has addressed the COVID-19 issue with tenacity and self-reliance. India has also proved how it rises to problems and capitalises on opportunities, as evidenced by the repurposing of diverse car sector firms to collaborate on developing life-saving ventilators.

The Hon'ble Prime Minister's clarion Call to use these challenging times to become Atmanirbhar has been well embraced, allowing the Indian economy to resurge. Unlock guidelines have been provided to restore economic operations while maintaining a high level of caution, allowing for gradual limitations.

All efforts have been made to ensure the information provided here is accurate. However, no guarantees are made regarding correctness of data. Please verify with scheme information document before making any investment.